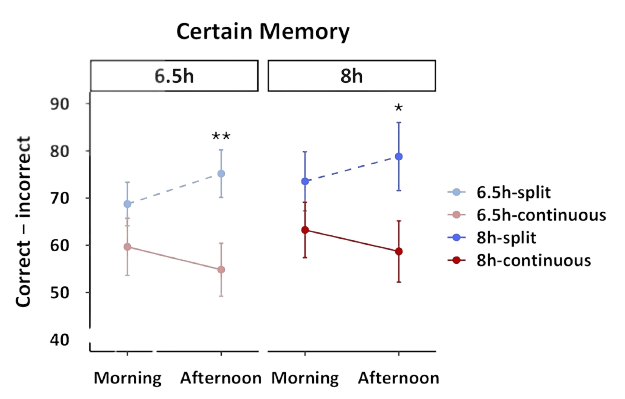

A group of researchers simulated a 2-week school environment, where adolescents were allowed set amounts of time, either split into a daytime nap and nighttime rest, or continuous nighttime sleep [1].

This paper (along with supplementary research) provides compelling evidence that an afternoon nap can greatly restore cognition, revitalize energy levels, and improve memory. We will first discuss the neuroscience of how daytime naps alter the nervous system, and then recommend a science-backed protocol for daytime napping.

Cognitive Encoding Capacity

Both groups of participants that divided their sleep into afternoon naps and nocturnal sleep (“split” groups) performed significantly better on afternoon memory tests than those who only slept during the night (“continuous” groups), regardless of whether they were assigned 6.5 or 8 total hours of sleep. This effect is what you may call “recharging your batteries,” and what I like to call “cognitive encoding capacity“.

It is important to remember that “brain-power” is finite; i.e, there are a set number of operations your brain can conduct before it begins to slow. This phenomenon could be explained by excess glutamate (the brain’s primary stimulatory/excitatory neurotransmitter) that accumulates in the prefrontal cortex, the part of your brain responsible for executive control and functioning. Since the brain cannot tolerate overexcitation, it begins to slow functioning; this is what we call “tiredness.” Researchers think sleep clears glutamate [2]. You can think of this as similar to how lactate builds up during physical exercise, and rest restores your muscles back to their full potential.

Another important takeaway from this graph: the “split” group did not perform worse on morning assessments than continuous groups, despite having technically “less” sleep at night. Consider this image:

Both groups still slept for a total of 8 hours; however, the split group divided 1.5 hours into the afternoon nap, meaning they only slept a total of 6.5 hours during the night. Despite this, they performed similarly to their peers (who slept the full 8 hours) during the morning recall assessment, while also performing better on the evening recall, taking advantage of the benefits of an afternoon nap.

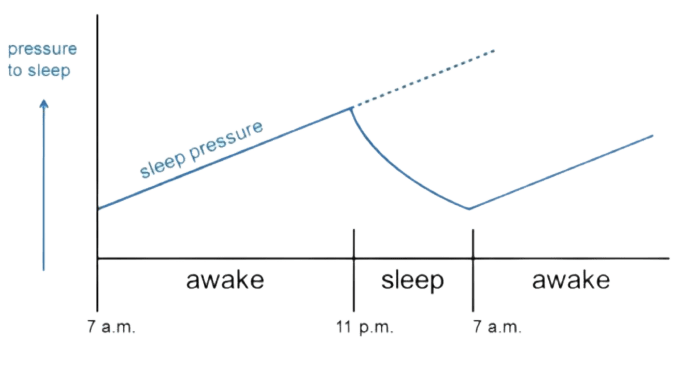

Homeostatic Sleep Pressure

Homeostatic sleep pressure provides another potential mechanism for the restorative benefits of afternoon naps. The CDC defines homeostatic sleep pressure to be:

“Pressure for sleep (homeostatic sleep drive) builds up in our body as our time awake increases (“sleep pressure” in Figure 2.3). The pressure gets stronger the longer we stay awake and decreases during sleep, reaching a low after a full night of good-quality sleep. The homeostatic process begins to build again after we awaken.”

However, research shows that a “full night” of sleep is not necessary to reduce homeostatic sleep pressure. Naps achieve the same benefit. By splitting up your sleep into multiple different

ATP (adenosine triphosphate) is the energy source for all cells in the body. When all three phosphates are broken off, adenosine is left over. This adenosine builds up in the blood stream and binds to adenosine receptors, inhibiting neural activity. Sleep reduces adenosine levels, thereby restoring energy levels and eradicating tiredness.

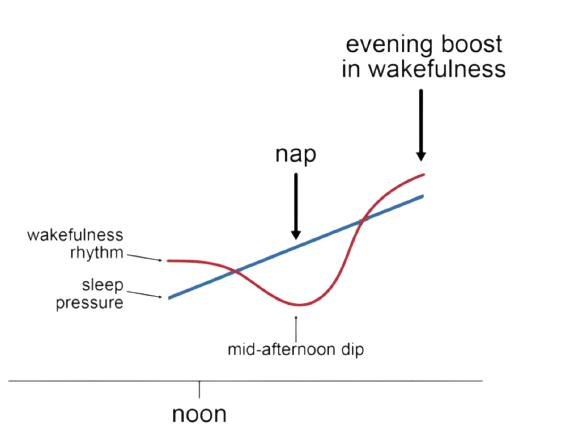

The Circadian Dip

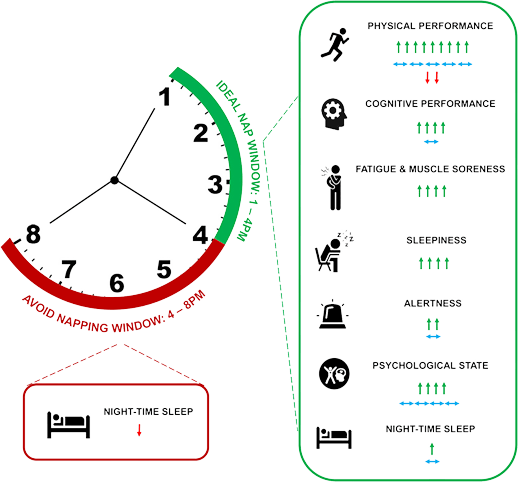

As pictured above, the circadian dip is an important physiological phenomenon that supports the idea of taking an evening nap. Energy tends to dip about 7-8 hours after waking time, which is the optimal time to clear adenosine levels. It is important not to force a nap, rather take advantage of regular biological patterns in order to fall asleep quickly and gain the restorative effect. The “ideal nap window” is between 1-4 P.M for most people.

Sleep Inertia and Post-Nap Planning

An important factor in the napping protocol is to designate a 30-minute post-nap period to dismiss “sleep inertia” [3]. A study on athletes who took naps found that they were much more ready to perform 2-hours post nap as opposed to 1-hour [4]. Thus, optimal performance can only be achieved after inertia wears off. The below graph [3] is helpful when planning. A general rule of thumb is that earlier is better so as not to ruin nighttime sleep while still gaining restorative effects.

Incorporating afternoon naps into your lifestyle has the potential to unlock greater cognitive abilities, memory, and sustained energy throughout the day.

Neurodegeneration

Neurodegeneration, or decreases in brain volume through neuron death, is a common aging-related occurrence. Unfortunately, neurodegeneration is associated with a variety of neurological disorders, like dementia, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s. A new study found a causal link between napping and larger brain volume based on nap-inclined genotypes. Although understudied, this connection might be an early indicator that afternoon naps can slow neurodegeneration. The authors estimate this effect to be equivalent to about 2.6 to 6.5 years of aging [5].

Subscribe to the Neo Neuron for weekly neuroscience-based advice.

References

[1] Cousins, J.N., Leong, R.L.F., Jamaluddin, S.A. et al. Splitting sleep between the night and a daytime nap reduces homeostatic sleep pressure and enhances long-term memory. Sci Rep 11, 5275 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84625-8

[2] Wiehler A, Branzoli F, Adanyeguh I, Mochel F, Pessiglione M. A neuro-metabolic account of why daylong cognitive work alters the control of economic decisions. Curr Biol. 2022 Aug 22;32(16):3564-3575.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.07.010. Epub 2022 Aug 11. PMID: 35961314.

[3] Lastella M, Halson SL, Vitale JA, Memon AR, Vincent GE. To Nap or Not to Nap? A Systematic Review Evaluating Napping Behavior in Athletes and the Impact on Various Measures of Athletic Performance. Nat Sci Sleep. 2021;13:841-862

https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S315556

[4] Davies DJ, Graham KS, Chow CM. The effect of prior endurance training on nap sleep patterns. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2010;5(1):87–97. doi:10.1123/ijspp.5.1.87

[5] Is there an association between daytime napping, cognitive function, and brain volume? A Mendelian randomization study in the UK BiobankPaz, Valentina et al. Sleep Health: Journal of the National Sleep Foundation, Volume 0, Issue 0 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S235272182300089X?via%3Dihub#sec0170

Leave a comment